Obituary

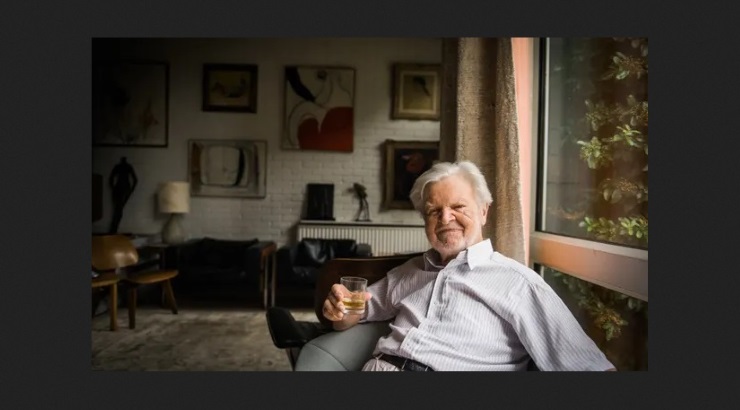

British Architect Who Designed JKUAT Towers Dies

Richard Hughes designed hundreds of buildings in East Africa.

Richard Hughes, a British architect who designed hundreds of buildings in East Africa, including the ICEA Building in Nairobi, died in May in the UK, his family said. He was 93.

His death closed an important chapter in the history of pre-independent Kenya’s architecture while marking the last day of life for a man who used vernacular architecture, which reflects local traditions, to push for multi-racial living in the country.

A liberal-minded architect, Hughes was committed to architecture that benefits the local community and he even established an architectural firm in Nairobi to promote it.

“Richard carefully designed with the conviction that every citizen deserved the best design, shaped by their social and cultural needs and the local environment,” Rachel Cass, Hughes’ granddaughter, wrote in the Guardian.

“He believed in design not as a luxury but as a powerful and relevant force for improving people’s lives.”

Born in London in 1927 to Dick Hughes, a land surveyor, and Olive Curtis, young Hughes moved to Nairobi with his family in 1939, when Kenya was still a British territory.

In the early 1940s, he attended Hilton College in South Africa and then worked briefly in Kenya before moving to London to study at the Architectural Association School of Architecture, the oldest independent school of architecture in the UK, from 1947 to 1953.

After two years of service at an architectural firm in Connecticut in the US, Hughes returned to Nairobi in 1955 to work for Blackburn and Norburn.

The following year, he founded Richard Hughes and Partners.

“From 1956 until his retirement in 1986, his Nairobi practice completed 275 buildings in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Sudan and Mauritius,” Cass said.

Some of his notable projects include the ICEA Building (now JKUAT Towers), Ufungamano House, ACK Kilifi, Hospital Hill, National Bank House, St Stephen’s Cathedral Kisumu, African Girls’ High School Chapel (now Alliance Girls’ High School), and the Kenya Federation of Labour Headquarters.

For the school chapel, Hughes adopted a traditional approach with thin stone walls set at zigzag and a large pitched roof reinforced by struts on stone piers. The struts and the roof rafters were made from telephone poles as a means to overcome budget constraints.

This, he argued, was a way of demonstrating how ordinary products of the modern world could be adapted to different cultural uses.

For the 19-storey ICEA Building on Kenyatta Avenue, Hughes established a structure with a strong climate-responsive design.

The office block, which is naturally ventilated, is designed to respond to the sun’s movement thus preventing high temperatures from building up in the workplace.

At the Krapf-Rebmann Memorial Church in Kilifi (now AIC Kilifi), he designed a structure that allows in a cool breeze from the Indian Ocean through slats in coral rag walls.

Hughes often built in Kikuyu areas, mostly inspired by post-war Brutalism. His church projects have been described as ‘fortress-like constructions with walls of natural stone which show a heavy, mechanically massive character’, which ‘express the aspirations of the Kikuyu’.

As a fifth-year student at AA School of Architecture, Hughes wrote a thesis that called for ‘an environment for multi-racial living’ in the form of a development plan for Maragua town.

On returning to Kenya, he joined the Capricorn African Society in an attempt to fight off both white supremacy and Black Nationalism and to push for the transition from white rule in Kenya to power-sharing via a multiracial electorate of the educated.

In 1956 Hughes acquired a secluded parcel of land on Kiambu Road to build a home for his wife Anne Hill, whom he married in 1951. The plot ran steeply down to one of the tributaries of Nairobi River and faced the Karura Forest on the opposite slope.

A concrete wall comprising huge rocks secured the house to the hillside, allowing a set of living spaces at treetop level with balconies and large windows looking over the quiet scene.

It was in this house, which naturalised nature for itself, where he sketched hundreds — if not thousands — of stunning pieces of designs that redefined East African architecture.

Hughes is survived by his second wife, Kavya Strout, whom he married in 2009 after the death of Anne in 2006; his children from his first marriage: Bridget, Penelope, and Mervyn; six grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.